Discover the story behind some of the objects and archives

in our collection

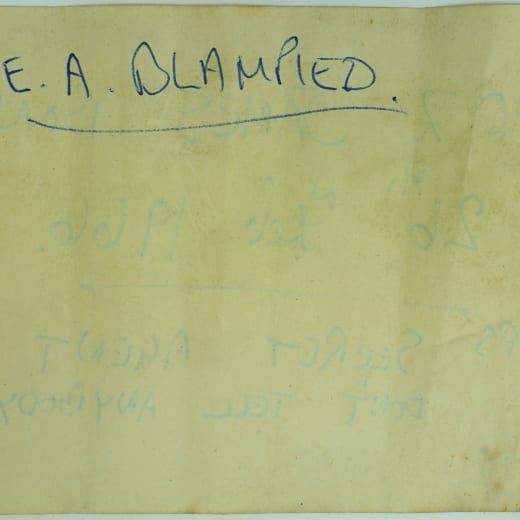

007 Note at Elizabeth Castle

The mystery of the James Bond note discovered during restoration work at Elizabeth Castle has been solved.

The daughters of Edward Arnold Blampied came forward following a public appeal by Jersey Heritage for help to identify the author of the note, which was uncovered when a fireplace was unblocked in the 18th century Officers’ Quarters at the fortress.

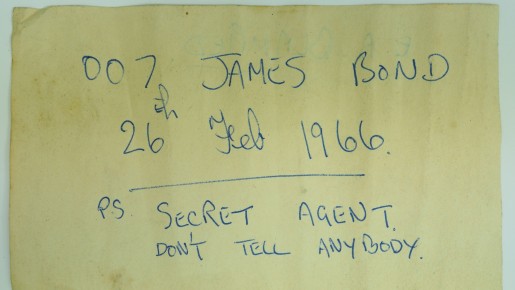

Annelis Michel and Debbie Blampied got in touch to say they believed their late father was the person who hid the note in the fireplace nearly 60 years ago. The note, which was originally in a glass bottle, reads: “007 JAMES BOND, 26th Feb 1966. PS SECRET AGENT. DON’T TELL ANYBODY.”

Side one of the note found

Edward was born in Jersey in 1937 and at the age of 17 signed up to the Royal Signal Corps, after having signed his own recruitment forms against his father’s wishes, in the early 1950s and saw active service during the Cyprus Emergency, for which he received the Cyprus General Service Medal, and was posted to the deserts of Iraq, prior to a spell of ‘home’ duty in Surrey.

This period of military service possibly explains why the 007 note was found with pages from the Reveille newspaper, as was first published during the Second World War as an ex-servicemen’s newspaper and continued to be published until the 1970s.

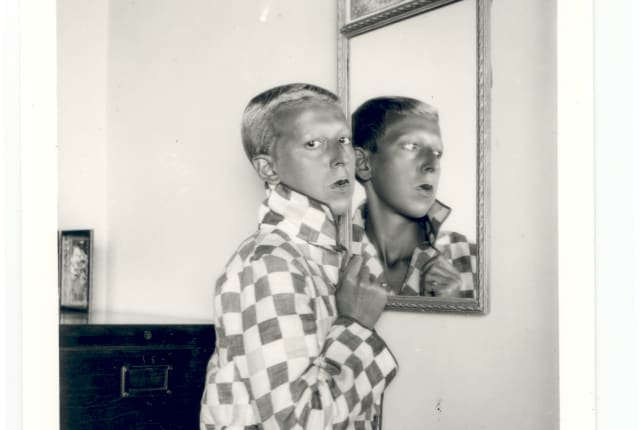

E A Blampied - In Uniform - image courtesy of Blampied family

After returning to Jersey, Edward was apprenticed as a carpenter with Stan Le Breton, though this was not his first brush with the trade, as the bar in soldier’s mess pictured was built by Edward during his time in Iraq.

In the Mess - image courtesy of Blampied family

Around the time of his marriage, c. 1960/61, Edward was working at Elizabeth Castle for the first time, whilst employed by the firm of Jimmy Watkins, and returned to the castle again in 1966 to construct the wooden stairways inside of the Officers’ Quarters, the building in which the 007 note was found. Debbie distinctly remembers her father taking her to visit Elizabeth Castle around 1972 and proudly showing her the carpentry work he had done at the site.

The Parade Ground and the Officers’ Quarters

Edward was an ardent James Bond fan, with his favourite film in the series being Thunderball, released in 1965, due to the diving scenes, which his wife fondly remembered that they went to the see the film at cinema at least twice. Edward was himself an avid diver and skilled carpenter, as he constructed at least three boats by hand.

So, why are we so sure that Edward Arnold is our mysterious E. A. Blampied? Well, according to his daughters, during the construction of their family home, which Edward undertook himself, they distinctly remember their father placing messages in bottles and other mementos within the walls of the house. Furthermore, during outings on the family’s boat, they remember their father encouraging them to throw messages in a bottle into the sea, in the hope that someone would read them and send a reply.

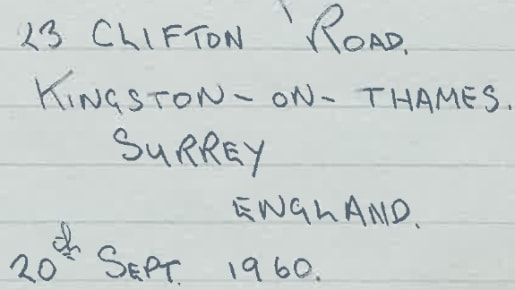

Unfortunately, Edward can’t confirm whether he did indeed leave the 007 note, as he sadly passed away in 1984 due to complications from a long-term illness. However, having compared an example of his handwriting with the note left at Elizabeth Castle, we are very confident that we have identified the author of the note, due to the very distinctive ‘th’ used after the date which is present on both the note and the letter used for comparison. In addition to this, there is a chance that we may find another of Edward’s notes at another of our heritage sites in the future, as Edward was also employed at Mont Orgueil Castle when renovation works were carried out there during the 1960s

An example of Edward's handwriting - image courtesy of Blampied family

Finally, in a remarkable coincidence, one of Edward’s grandsons is currently working as the Junior Project Manager at Elizabeth Castle with Building Renovations and one wonders whether he will likewise carry on his grandfather’s tradition of leaving notes within the castle!

E A Blampied - image courtesy of Blampied family

History

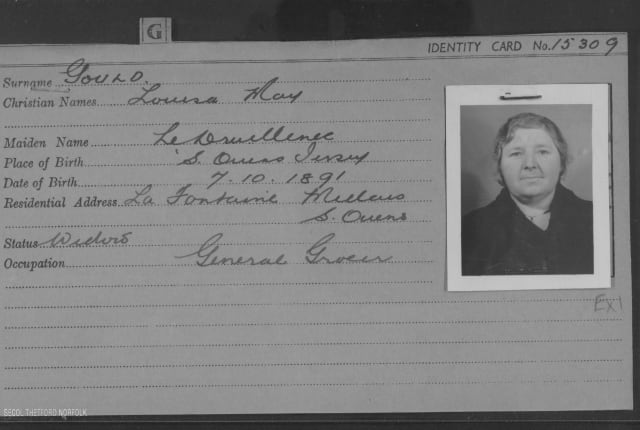

Island at war

The Channel Islands were occupied by Nazi forces during World War II, read one woman's extraordinary story.

History

Corn riots

Learn about the corn riots of 1769, why they happened and how this public protest inspired change.