A two-person resistance campaign lead by two artists during the Occupation of Jersey

Claude Cahun (1894-1954) was an artist, photographer and writer. Creating some of the most startlingly original and enigmatic photographic images of the twentieth century, Cahun is best remembered today for their unique self-portrait photographs, in which they would appear as different characters, challenging notions of gender and identity and typical stereotypes about women.

This defiance of convention and authority was not limited to art however and was characteristic of much of Cahun’s life. Around 3 years after Cahun and their partner, Marcel Moore, moved to Jersey in 1937, the Island was invaded by German forces and occupied for nearly 5 years. Cahun and Moore wanted to resist the German authorities right from the outset of the Occupation because, despite their quiet and uneventful life, they felt compelled to act against the suppression of liberty and freedom. Cahun believed that not all of the German soldiers stationed in Jersey were Nazis and with some inspiration, could be encouraged to overthrow the Nazi regime on the island. So began a two-person resistance campaign that could have ultimately led to their deaths—especially courageous as Cahun had been born into a Jewish family, although did not declare themselves as Jewish as required by German order in October 1940.

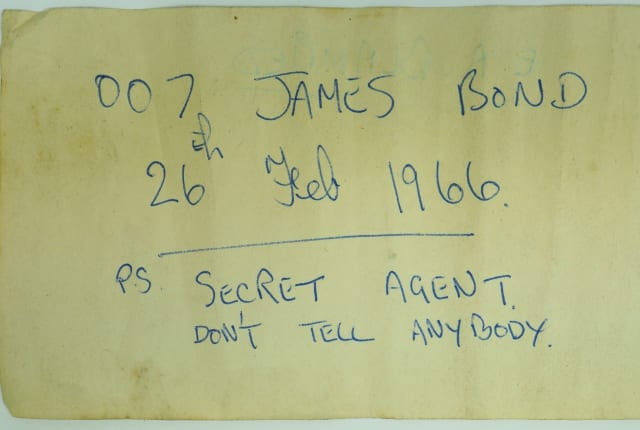

In June 1942, the occupying forces decreed it illegal to be in possession of a radio set. Cahun and Moore retained a radio set in their home however, and used this to listen to BBC broadcasts. Moore had not declared that she was fluent in the German language and she used this skill to translate news taken from radio broadcasts and Cahun would convert this into poems and other witty pieces of writing. The words were typed or handwritten onto small sheets of tissue paper and Moore would sometimes add illustrations. They intended these notes to seem as though they were written by a German officer from within the occupying forces and they were signed der Soldat ohne Namen (the Soldier with no Name).

The notes were distributed by Cahun and Moore themselves. They made special trips into St Helier where they were able to deposit the notes more easily amongst crowds of people. They would leave the notes in soldier’s coat pockets and on café tables. As the Occupation went on and tobacco became an increasingly rare commodity, they discovered that by placing notes inside cigarette packets they were more likely to be picked up and read.

Jersey Heritage have a selection of over 50 of Cahun and Moore’s original resistance notes within their archive collection. A few of these are examined in further detail below.

In this note, which features an illustration of a sinking ship, Hitler is the subject of the joke. The note plays on a well-known German folktale about the ‘Lorelei’ – a type of siren that would sit on the banks of the Rhine River and lure sailors to their death. Most soldiers in Jersey would have been aware of this folktale and here Cahun has written:

“I believe in the end the waves

Devoured both sailor and boat

And that was brought about

By Adolf Hitler with his screaming.”

Through this parody, Hitler is luring sailors to their death, and not with a beautiful song, as in the traditional tale, but with his ranting and screaming. The poem seeks to emasculate Hitler, by putting him in the place of a well-known female character.

Hitler is the subject of the joke in this handwritten note

Another of their resistance notes reads:

“Hitler leads us

Goebbels speaks for us

Goring eats for us

Ley drinks for us

Himmler? Himmler murders for us

But nobody dies for us!”

This is seeking to stir up disillusionment between the soldiers and their leaders, by highlighting the gap that exists between them and by pointing out how the ordinary soldiers are being exploited.

Written to stir up disillusionment between the soldiers and their leaders

Other resistance notes openly threatened the occupiers as can be seen in this example which reads:

“The cowardly police bureaucrats who thrive on lies and shameful cruelty will be destroyed by the soldiers with no name.”

A note that openly threatened the occupiers

Their resistance activities also took other forms. One of the Island’s labour camps was positioned only a short distance from Cahun and Moore’s home, La Rocquaise, and the slave workers housed there suffered horrific treatment, malnutrition and poor health. Cahun and Moore frequently distributed food to the prisoners under cover of darkness, during the hours of curfew.

Cahun and Moore used the location of their home to great advantage. La Rocquaise was located right next to St Brelade’s cemetery, which was designated the final resting place for German soldiers who died in Jersey. In fact, the section of the graveyard given over to the German dead lay directly beside their house and they frequently watched military funerals through their windows. They took the opportunity to deposit more of their notes in the German staff cars parked outside their home. Their personal danger was heightened by the fact that a Soldatenheim, a type of social club, was located at the St Brelade’s Bay Hotel opposite their home.

Cahun and Moore managed to evade detection for a number of years, but their luck did eventually run out and they were both arrested at their home on 25 July 1944. Their trial took place on 16 November 1944, during which the pair were sentenced to death for activities undermining the German forces and six months imprisonment for possessing a radio and listening to the BBC. On hearing the sentence, Cahun, with typical dry humour, asked which of the sentences should be carried out first.

Between November 1944 and January 1945, Cahun and Moore lived with an ever-present fear of execution but nevertheless rebuffed all efforts to persuade them to appeal their death sentence. The French consul and the bailiff intervened on their behalf however, and on 20 February, Cahun and Moore were informed that the German high command had granted them a reprieve. They continued to serve their prison sentence until the Island was liberated on 9 May 1945.

During their time in prison, Cahun had befriended a German soldier, a fellow prisoner, who had given them the badges from his uniform. After the war had ended, Cahun posed for a photograph outside their home, with one of these badges clutched between their teeth – a final act of defiance. This photograph sums up much of Cahun’s life, which was characterised by resistance and rebellion.

A selection of the original notes can now be in seen in our new exhibition at the Jersey Museum – La Tèrr’rie d’Jèrri – d’s histouaithes dé not’ Île / Being Jersey – stories of our Island.

Claude Cahun, Self-portrait with Nazi badge between teeth, Jersey 1945