Through a fissure in the rock face, archaeologists found a time capsule, a paleolithic (or early Stone Age) site that contains 250,000 years of evidence of human life in Jersey

Coastal Neanderthals at La Cotte

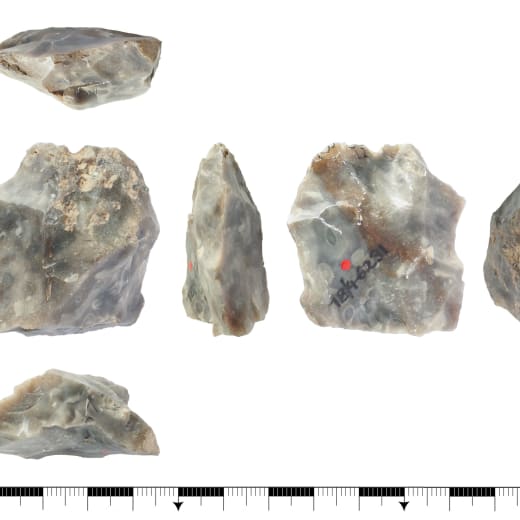

Small core of flint from which flakes have been removed in an organised way to prepare the core for removing useful flakes from its surface. This method, known as Levallois technique, is used reguarly in some of later levels at La Cotte, but is much rarer in earlier occupation episodes. This core is special because is comes from Layer H , the earliest period of Neanderthal habitation so far identified at La Cotte. It dates to a warm period, known as MIS 7, maybe as much as 240,000 years ago, Jersey was not yet an island, but a peninsula surrounded by high-sea levels. Woodland including oak, hazel and elm surround La Cotte.

Neanderthals Adapting to a Cooling Climate at La Cotte

A flake modified along one edge to create a tool with a convex scraping surface. This relatively large flake, from Layer E, has been further modified to thin the back of the flake, perhaps to make it slightly easier to hold. It comes from a Layer E, an episode of habitation at La Cotte, rich in flint artefacts preserved in a soil, dated to the start of the cold stage we call MIS 6 around 190,000 years ago. The colder conditions are indicated by the presence of woolly rhinoceros, but some deciduous woodland is still present around La Cotte. A tool like this could have been used to clean hides at the start of the processes of turning them into clothing or parts of tents.

A Knapping failure that reveals Neanderthal technology at La Cotte

A fragment of a Levallois core set up to remove flakes from both ends. This artefact represents a knapping mistake by a Neanderthal tool maker, resulting in the breaking of the core. It’s important to us as it is the only clear evidence we have the production of elongated flakes was being undertaken. The blades could have been used as cutting tools. It comes from Layer A at La Cotte, an episode of repeated occupation of the cave around 180,000 years old leaving behind a rich record of stone artefacts and bone. Animals being butchered at the site include mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, reindeer and red deer. Abundant burnt bone indicates Neanderthal people were living in the cave at this time.

Processing Mammoths with small, specialised tools at La Cotte

A specialised flake removal known as burin spall. This has been expertly driven down the edge of a flake. It was used either to create a pointed working surface, rejuvenate a blunted tool-edge or to be used as a small tool in its own right. This find was made from Layer 3, relating to a period of dramatic climatic cooling during MIS 6 around 170,000 years ago. It is associated a mammoth bone heap. No large cutting tools were found at this level but there was lots of evidence for the use of small tools like this, more suited to processing parts of carcasses rather than the initial stages of butchery. Horse, artic fox and red deer were present in the cold landscape at this time. Pollen indicates an open landscape of willow, grasses and heather, with a few birch and pine trees.

A valued tool, carried to, and discarded, at La Cotte

Thick, elongated point, flaked to create two sharp, convergent sides. One of a a group of similar points from Layer 5. This one shows some damage to the tip which Paul Callow speculated could have been produced from use of the tool as a spear-head. Although possible, it is hard to see how some a thick artefact could have been easily hafted. It appears to be a valued tool, resharpened many times and then thrown away because the edges were too steep and blunt to be useful. The tool was found alongside the upper bone heap, some perhaps it could have been used as part of the butchery of the mammoth carcass. This tool came from a short episode of use of the cave during the MIS 6 cold stage, maybe around 160,000 years ago. Very little pollen from trees was present in this sample, it being dominated by heather and willow, indicating very cool conditions.

A rare biface from La Cotte de St Brelade

Excavated in 1910 during the first of two seasons orgnaised by the Société Jersiaise, this stone artefact comes from layers of Neanderthal occupation which date to between 100,000 and 40,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age. The tool is made on a nodule of relatively high-quality flint, not found naturally in Jersey. It has been shaped on both sides using a soft hammer, perhaps made of antler to produce a cutting tool, held in the hand. Multiple stages of reworking are evident including flake removals to resharpen the tool leading to the twisting of it’s cutting tip. We interpret this as a valued tool, carried for a period of time by a late Neanderthal person before being discarded at La Cotte. Bifaces are a feature of some late Neanderthal cultures, but few are found at La Cotte, further study of the waste flakes from these assemblages might help to show if other valuable tools like this were being reworked, but not thrown away at the site.

A Late Neanderthal processing tool from la Cotte

Excavated in 1910 during the first of two seasons orgnaised by the Société Jersiaise, this stone artefact comes from layers of Neanderthal occupation which date to between 100,000 and 40,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age. The tool is made on high-quality flint, which must have been carried to the site. A boldy struck flake forms the basis of this tool which has then been modified on two sides of the tool, a process we call retouch. The retouch created edges which would not be as sharp as the original flake, but very well suited to processing acivities. This tool could have been used to prepare hide, remove flesh from bones or to process other organic material. Detailed microscopic analysis could shed light on it’s use as well as whether it was hafted, or just held in the hand.

Dr Matt Pope

Dr Matt Pope works for the Institute of Archaeology at UCL, London. He studies early human behaviour and how prehistoric people adapted to changing environments. He is particularly interested in the evolution of human hunting behaviour and the use of landscape. He teaches the archaeology of human evolution and coordinates multidisciplinary field investigation. He is passionate about sharing the results of human origins research and explaining why understanding human adaptation is important to society.

Dr Beccy Scott

Dr Beccy Scott works in the Department of Prehistory and Europe at the British Museum, specialising in the behaviour of early Neanderthals in North West Europe. She is particularly interested in how Neanderthals came to ‘act like’ Neanderthals, using their stone tools to reconstruct how they moved within their landscapes, and modified their environments. Beccy investigates the texture of Neanderthal landscapes beyond river valleys and excavates sites on the upland interfluves of Southern Britain. She has studied Neanderthal technology from Britain, Northern France and Belgium, as part of the AHOB projects, and is the author of ‘Becoming Neanderthals’.

We know it is one of the most important Ice Age sites in Europe, but we don’t yet know all the secrets it holds. This project has the potential to surprise us with incredible new stories.

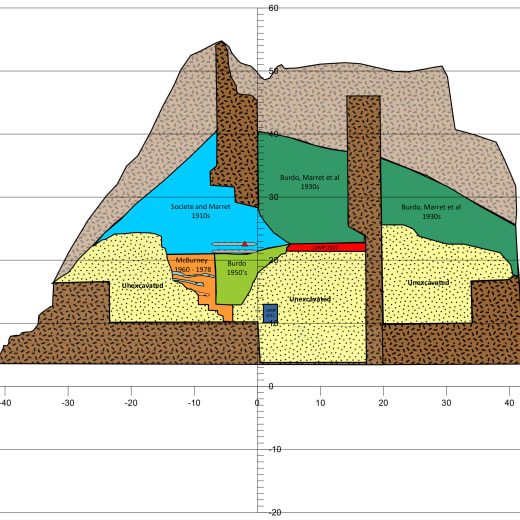

In 2010, the Ice Age Island team began to survey La Cotte de St Brelade, determining both that the site contained further Neanderthal archaeology and that it was under threat from significant coastal erosion. Since then, we have worked with the Société Jersiaise and engineering teams from the Channel Islands and UK to transform the site into a place that is both safe to work in and secure from further damaging erosion. The engineering project represents a bold and innovative response to the effects of sea level rise and climate change and provides an opportunity to safeguard an internationally important scientific record.

The return of the archaeologists was only possible after the cliffs above were made safe and the site was protected from the sea. The sea wall has been designed to protect the site from sea level rise and storm events during the next few decades, and this will give us time to discover more about this internationally important record of Neanderthal archaeology and leave the site intact or future generations to make their own discoveries.

The sea wall shown on the right by Dave Ferguson at the Jersey Evening Post

Working on a part of the site that hasn’t been accessible for over a generation years, we’ve been able to begin to detailed, scientific excavation, recovering scientific dating samples and finding artefacts made from flint and quartz. The excavations are part of a long-term plan for stabilising the West Ravine and the team are now taking on this this complex and massive site, bringing it under new investigation and preserving it for the future.

Working on site on the West Ravine

In July 2022, we announced that The former Prince of Wales had become Patron of this important restoration project to protect and preserve the ancient site of La Cotte de St Brelade. At the time, Jersey Heritage’s Chief Executive Jon Carter gave thanks for the “tremendous boost” this news would give the project.

The two-year patronage came to its end in 2024 and we are incredibly grateful to The former Prince of Wales for helping us to gather interest in, and support for, the La Cotte de St Brelade Archaeological Project as it moves on to the next crucial stage.

His Royal Highness The former Prince of Wales at Highgrove by Hugo Burnand