Marcel Moore, her art and life

From 1913, Moore began publishing illustrated articles on fashion in the regional newspaper Le Phare de la Loire which was edited by Cahun’s father, Maurice Schwob. Three fashion illustrations from 1915 and 1916 show a sureness of line, subtle use of colour and shade. They anticipate the boyish fashions in clothing and hairstyle known la mode garçonne which was to sweep postwar Paris.

Click on images to expand.

Postwar French society was in turmoil. More than one and a half million French soldiers died during the First World War. In an attempt to defend the role of the family in society, the government introduced strict laws banning birth control, abortion and pornography. Women were legally and financially subordinate to men.

Cahun and Moore had completely different experiences of the First World War. Cahun spent the war studying literature at the Sorbonne University in Paris. Moore worked as a nurse for the 6th Artillery Regiment, exposed to the horrors of a wartime hospital.

The War necessitated a radical change in fashion and accelerated the widespread adoption of dress innovations already introduced by progressive designers and adopted by the upper classes. Fashion magazines suggested that wartime fashion should be rational, practical and simple. This meant the end of the corset, a new shorter hemline (particularly practical for nurses like Moore, whose long skirts were considered unhygienic) and the use of the suit as women’s uniform on the home front. Moore’s fashion illustration of 1915 aptly displays the new fashions’ comfort, ease of movement and practicality. However, a key characteristic which differentiates this design, is that the model wears trousers. Women wearing trousers was illegal in France up until 2013 (yes, really!). In the 1920s and 30s French women could wear trousers as part of their holiday wear but they were not acceptable for women in cities until much later in the century. The actress Marlene Dietrich was asked to leave Paris by the police because she wore trousers in public. In Moore’s design, the boyish figure stands relaxed, hands in pockets showing the comfort of the outfit. The piping along the trousers seams and around the collar is suggestive of military clothing. Many designers took inspiration from the austerity of military clothing.

In 1917, Moore and Cahun became stepsisters when Moore’s widowed mother married Cahun’s divorced father. This entwining of the two daughters facilitated their artistic collaborations and provided a cover for their intimate relationship. In the same year, Moore and Cahun moved into a flat on the top floor of the office building of Le Phare de la Loire at the Place du Commerce in Nantes.

In 1918, Moore registered at the École des Beaux-Arts in Nantes. She studied painting, drawing and woodcutting. She was particularly talented in drawing and was influenced by the work of William Blake, Paul Gauguin, Aubrey Beardsley and William Morris.

Moore and Cahun’s first joint publication was in 1919. It was a book entitled Vues et Visions, which had been published as an article in the literary journal Mercure de France in 1914 when Cahun was writing under the pseudonym Claude Courlis. Moore provided illustrations for the book version of the essay. Her illustrations frame each page written by Cahun, forming a sort of theatrical proscenium and present juxtaposed paired vignettes of old and new. In this image two weathered skiffs tethered to an abandoned pier in Le Croisic contrast with stone figures of two boys permanently united in loving proximity upon a tomb in ancient Greece. This book has been seen by some as Cahun and Moore’s artistic ‘coming out’, as it raised their profile as an artistic couple, and indirectly confirmed their affection for each other and the legitimacy of their bond. The book’s dedication is most telling. Cahun wrote: ‘”To Marcel Moore” I dedicate this puerile prose to you so that your designs may redeem my text in our eyes.’ The intermingling of possessive pronouns reflects the intermingling of text and images in the book, further echoing the intimacy of their relationship.

Click on images to expand.

In 1922, Moore and Cahun moved from provincial Nantes to metropolitan Paris. The stepsisters circulated within the vanguard artistic circles of Parisian life and were particularly active in theatrical and political groups. Their address book attests to their association with many leading figures in the cultural and intellectual milieu of interwar Paris with addresses listed for André Breton, Sylvia Beach, Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dali, Robert Desnos, Paul Eluard, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti, Aldous Huxley, Henri Michaux, Man Ray, Chana Orloff and Gertrude Stein. It also lists several members of the theatrical establishment – Edouard de Max, Marguerite Moreno – and experimental theatre – Pierre Albert-Birot, Georges and Ludmilla Pitoëff. Moore created many portraits and costume designs for actor Edouard de Max, who specialised in roles of decadent emperors, like Nero and Heliogabalus and even appeared almost naked on stage in Jean Lorrain’s Prométhée. De Max surrounded himself with young homosexual artists. André Gide wrote his homosexual play Saül for de Max in 1898, although no theatre produced it until 1922. The interwar French homosexual movement was led by those in artistic circles.

Click on images to expand.

Moore often put her graphic style to good use by creating advertising material for various theatrical productions. The American expatriate dancer Beatrice Wanger used the stage name ‘Nadja’ and performed mostly for the Theatre Esoterique. Moore created handbills, posters and postcards featuring the dancer. An American journalist, Golda M Goldman, writing for the Chicago Tribune in 1929, in an article entitled ‘Who’s Who Abroad’, wrote: ‘In order to appreciate to what extremely decorative lengths the art of poster design can be carried one must study a group of pictures by the young French woman who signs her work simply “Moore”.

‘To call such work poster work is almost a misnomer, for in it Mlle Moore shows a capacity for portraiture, a mastery of line both delicate and strong, a great pictorial effectiveness, and a beautiful use of colour.’

Click on images to expand.

In 1929, Moore and Cahun joined the avant-garde theatre group Le Plateau, which was directed by Pierre Albert-Birot. Albert-Birot set out his ideas for a theatre based on dramatic and poetic expression in the theatre’s magazine also called Le Plateau. Cahun contributed writings to this publication and Moore provided portraits of members of the company.

Moore and Cahun published their second major collaborative publication in 1930 – Aveux non Avenus (variously translated into English as ‘Disavowed Confessions’ and ‘Unrealised Avowals’). Again, Cahun wrote the text, the photomontages that illustrate the book were probably collaborative works. Golda M Goldman wrote: ‘At present the artist is engaged in making a series of distorted photographs of her sister, which probably will be used to illustrate the volume Aveux non Avenus, which Claude Cahun is publishing later this year. Entirely printed by herself, these photographs are something quite new in this field.’

R.C.S. (fear) from Aveux non Avenus, 1930

In the 1930s, Moore and Cahun became involved in several anti-fascist groups. In 1932, they joined the Association des Ecrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires, where they met surrealist leader André Breton. Occasionally Moore signed the political pamphlets written by Breton, with much input from Cahun. Whilst Cahun was active in taking part in meetings, demonstrations and publications, Moore was active behind the scenes.

In 1937, Moore and Cahun left Paris for Jersey. They purchased a house, La Rocquaise, in St Brelade’s Bay. They knew Jersey from many childhood holidays spent here. Perhaps they were disillusioned with the political climate in Paris and disturbed the political divisions causing their circle of friends to break up and the rise of fascism. While living in Jersey, the stepsisters tended to call themselves by their birth names. Moore was even known by some as ‘Bertie’ a shortening of her second name Alberte. Although they had a small circle of mostly French-speaking friends and often held card playing evenings, they were a private couple. They were known locally as being a bit strange, wearing modern clothing (trousers for example!) and nude sunbathing. Moore and Cahun corresponded with friends in Paris and were visited in Jersey by Jacqueline Lamba, surrealist painter and married to André Breton, and by Henri Michaux, a poet and artist. However, their sanctuary was disrupted in 1940 when German forces invaded Jersey. Moore and Cahun made a conscious decision to remain in the Island rather than returning to Paris or evacuating to England.

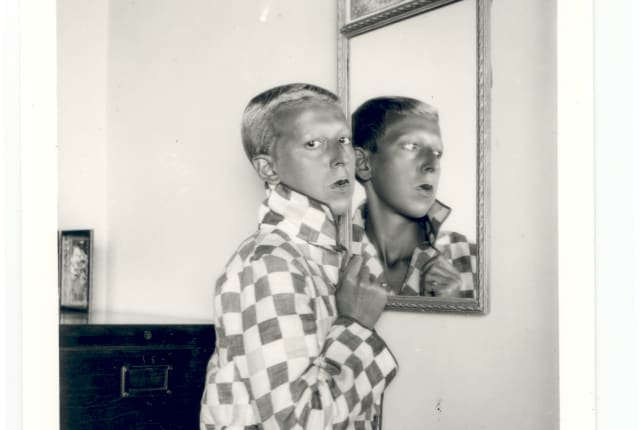

Cahun and Moore, self portrait

Much of their political activity in the 1930s had been anti-fascist in nature. During the Occupation they put much of this anti-fascist sentiment into actual resistance by carrying out counter-propaganda activities aimed at demoralising German soldiers by suggesting that there was a feeling of unrest and simmering dissention amongst the German ranks. A Jersey Weekly Post journalist interviewed them in July 1945 and described them as ‘animated by a burning love of their country and a deep hatred of the Boche’. Moore described how they started their activities: ‘It all started in 1940 in a small way and grew as time went on…We always listened to the BBC and any other news we could get which was not tainted by Boche propaganda, and it made us perfectly sick to hear the so-called “news” put out by Radio Paris, so we decided to run a news service of our own for the benefit of the German troops. We were inspired by the broadcasts by “Colonel Britton” on the European service of the BBC and used to take the salient points, translate them into German on small pieces of paper which were typed by my sister, and sign them “The nameless German soldier.” We distributed them by placing them in cigarette paper cartons, match boxes, and so on and placed them in German cars when and where we could. We used to make special trips to St Helier for this purpose.’ Moore had defied a German order for all German speakers to declare themselves, so when the Germans questioned this section of the population, she remained undetected. The tracts they produced evolved over the years and as well as passing on news, the stepsisters wrote poems and anti-propaganda statements. They would produce multiple copies of the same tract by using carbon paper in their typewriter. Cahun reflected in ‘Le muet dans la mêlée’ in 1948: ‘The Underwood allowed for ten to twelve carbon copies in one single go…Knowing that I could not give the police the impression of several typewriters, I made an effort to vary the way of tapping the keys and the presentation to give the impression of several typists.’ Moore and Cahun used the location of their home to good advantage. La Rocquaise was next to St Brelade’s Church and cemetery, which is where the Germans also had their military cemetery. During funeral services they would drop their leaflets into German staff cars.

Click on images to expand.

Cahun and Moore continued these activities until 25 July 1944, when Cahun believed they were informed upon by the vendor of the cigarette paper – the usual wrappings for the tracts. On that day they had been into St Helier to distribute their propaganda. On the way home, their bus was stopped and searched by the Gestapo. As Cahun wrote in 1948: ‘The vendor of these cartons had indicated to them the activists. We recognised her on the bus. It is clear that this is where it happened. A German military took the bus, the one taking us back to St Brelade. During the trip he inspected the identification documents of the passengers – commonplace enough not to alert us. Thus they had confirmed the suspect name.’ That evening the Gestapo searched their house and found a suitcase containing several propaganda tracts. Cahun and Moore were arrested and taken to Gloucester Street prison. They had anticipated their arrest and resolved to commit suicide. They had set aside a ‘mortal dose of barbiturates’ disguised in a Milk of Magnesia bottle. After brief questioning, Cahun and Moore were put in a cell, where they were found unconscious later that night. Their hospitalisation delayed their trial, and probably also prevented them being deported to a prison camp as by the time they were both well enough to stand trial, the Allies had liberated St Malo. Shortly after being released Cahun was once more hospitalised when a German doctor prescribed too-strong medicine for Cahun’s bladder disorder. At the same time, Moore once again tried to commit suicide by cutting her wrists. When not hospitalised, the women were in solitary confinement. Their trial eventually started on 16 November 1944. Moore told the Jersey Weekly Post reporter in 1945: ‘We were taken for trial, if you can call it a trial; all they did was read out our statement and sentence us. A German officer was detailed to ‘defend’ us and he told the court that it “most unpleasant to have to defend such people”.’ Moore wrote to Paul Levt in 1950 that ‘the prosecution is much more bitter against us than the prosecution’, and that one of the judges Oberst Sarmsen summed up saying their actions ‘could not be considered as a moral crime…You are franc-tireurs [partisans]…even though you used spiritual arms instead of firearms. It is indeed a more serious crime. With firearms, one knows at once what damage had been done, but with spiritual arms, one cannot tell how far-reaching it may be’. They were sentenced to death for undermining the morale of the German forces, six months penal servitude for listening to the BBC and to six months for having arms and a camera. Moore and Cahun refused to sign letters of appeal. The Bailiff sent a plea for clemency and the French Consul, Henry Duval, met with Baron von Aufsess, the Head of Civil Affairs in the German Field Command, to talk about a reprieve. In February 1945, the stepsisters learnt that their death sentence had been commuted to life imprisonment. Moore and Cahun remained in prison until the very last day of German Occupation. They were eventually released on 8 May, just 15 minutes before Winston’s Churchill’s famous speech. They returned to a home that had been pillaged by German soldiers.

Cahun died in 1954, leaving Moore to spend the rest of her life alone. Moore moved to a smaller house, Carola at Beaumont. There are no artworks dated during this period, but the photographs Moore created are lonely in atmosphere, much as Moore seems to have been without her lifelong lover Claude Cahun. Marcel Moore took her own life in 1972.

Photograph of St Aubin’s Bay, around1965 by Marcel Moore