Discover the story behind some of the objects and archives

in our collection

d’Auvergne’s Travel Chest

A leather travelling chest that once belonged to Vice-Admiral Philippe d’Auvergne (1754-1816).

Earliest known drawings by Blampied

In September 2025, the two earliest known drawings by artist Edmund Blampied were donated to Jersey Heritage for the art collection

Victoria Cross awarded to Jack Counter

Jack Thomas Counter was awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest order of gallantry, for his actions during the First World War in 1918

Witches Rock Postcard

In the parish of St Clement, near Green Island, there is a large rock formation steeped in legend

HMS Havick Wreck Material

Havik was an 18-gun sloop-of-war, launched in 1784 for the Dutch Navy. Upon completion, she was transferred to and served in South Africa.

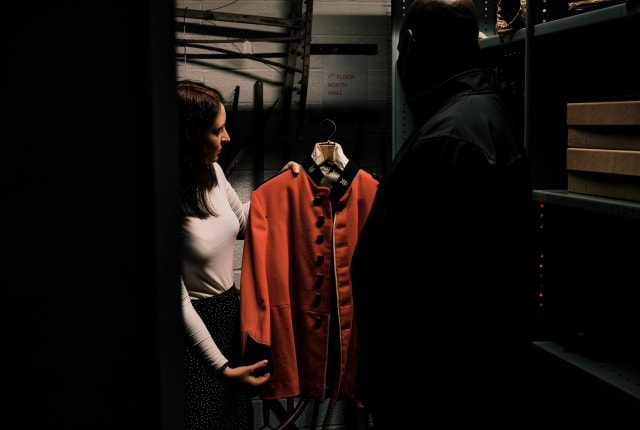

Militia Jacket

A significant part of the museum’s military collection is the Government of Jersey’s Public Works collection.

Bronze Age spearhead

In August 2020 Jay Cornick, a local metal detectorist, brought in a three-thousand-year-old bronze spearhead he had found while detecting on

Secret stamps

At first glance, it may seem an object of interest only to stamp enthusiasts...

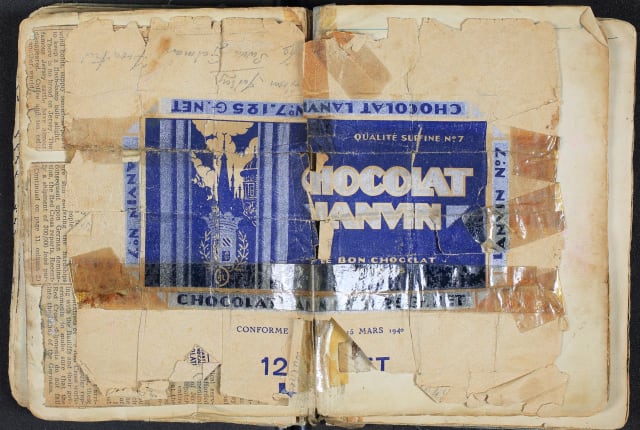

The Chocolate Wrapper

Tis scrap of paper is, as far as we know, the only detailed record of a young Jerseyman’s deportation.

Adèle Haarseth’s Story

In a change to the normal object in focus, we’re taking a closer look at the life of Adèle Haarseth, née Pallot.

Accessories handmade in Wurzach internment camp

These colourful bags, shoes and other accessories are part of a collection of items handmade by Nellie May Faulder.

Wartime Gift

Princess Mary Gift Boxes, which were created in 1914 and intended to be distributed as a Christmas gift to all soldiers on active service.

Resistance notes

A two-person resistance campaign lead by two artists during the Occupation of Jersey

Victoria Cross

Instituted by Queen Victoria in 1856 by Royal Warrant, the Victoria Cross is the highest military decoration awarded for valour to members o

Sir Anthony Paulet Portrait

The oldest portrait in the collection can be found at Mont Orgueil Castle and depicts Sir Anthony Paulet, Governor of Jersey.

Palace Hotel Letter

A letter donated to Jersey Archive in May 2024 may have finally revealed the truth about an infamous hotel fire...

Royal Charters

Royal Charters were issued by the Monarch as a solemn grant of land, privileges, exemptions or immunity.

Russian Toy

Learn about this traditional Russian wooden toy made by prisoner-of-war.

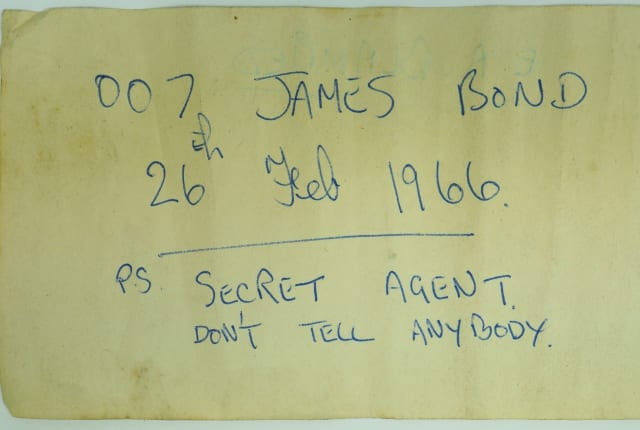

007 Note

The mystery of the James Bond note discovered during restoration work at Elizabeth Castle has been solved.

Medals

Jersey Heritage have acquired a new collection of medals at auction awarded to Jersey woman, Florence Puddicombe, for nursing service.

PS Normandy porthole

The PS Normandy was a British paddle-wheel steam ship built in 1863.

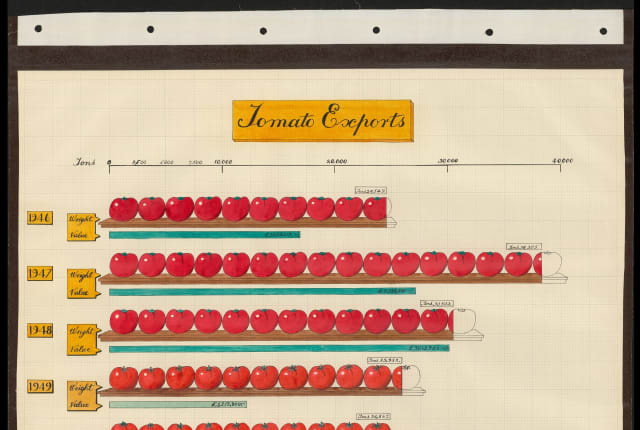

The Tomato Book

Affectionately known by Archive staff as the ‘Tomato Book’, this document is from the States Impôts Department.

Clifford Cohu’s watch

The story behind a pocket watch which belonged to Canon Clifford Cohu.

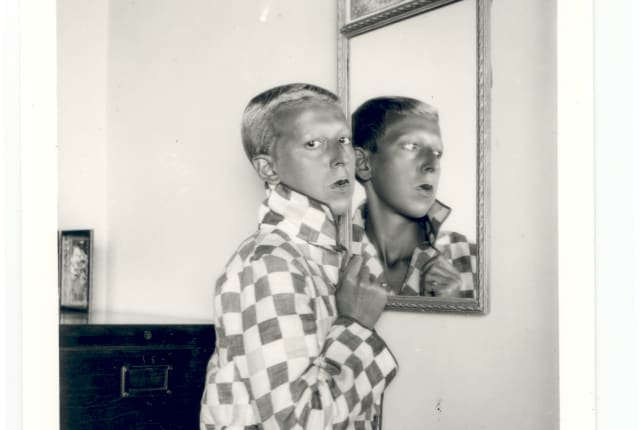

Cahun Photographs

Discover the story behind our collection, this month we take a closer look at Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore.

Aunt Elizabeth by Edmund Blampied

One of Jersey’s most iconic 20th century artists, Blampied is best known for depicting scenes of rural Jersey life.

Samplers made by Jane Mary Barreau, 1826

We have over 90 samplers in our textile collection, the oldest of which dates from 1736 and the most recent 1943.

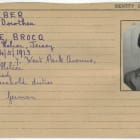

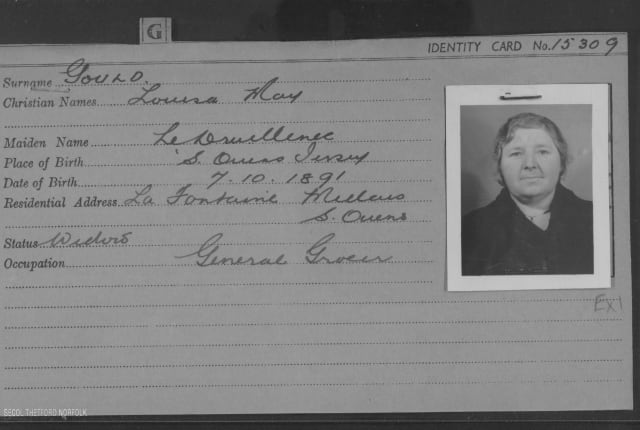

Louisa Gould’s Registration Card

A story of bravery and betrayal during the Occupation.