Discover the story behind some of the objects and archives

in our collection

The envelope, the secret stamps, and the woman in hiding.

At first glance, it may seem an object of interest only to stamp enthusiasts: an envelope for a registered letter, marked with six red 1d. stamps issued during the Occupation, and three Jersey postmarks. But this is no ordinary piece of mail. Not only does it hold a secret act of wartime resistance, but it also represents a link to one woman’s extraordinary story of survival during the Occupation of Jersey.

The envelope is a first day cover; a collectable item of philatelic interest which marks the first official use of a new stamp issue. It bears six vivid 1d. reds, issued on 1 April 1941. These were the first postage stamps issued by the German authorities in the Channel Islands during the Occupation. Alongside them is a registered mail label numbered 0007, and three circular date stamps confirming the envelope’s status as a first day cover.

Designed by Major Norman Rybot and printed locally by the Evening Post, the red 1d. stamps were created in March 1941 and released on 1 April. On the surface, they served a practical need. Jersey, cut off from mainland Britain, was rapidly running out of postage stamps, and so the German occupying forces ordered the Bailiff to commission a wartime issue.

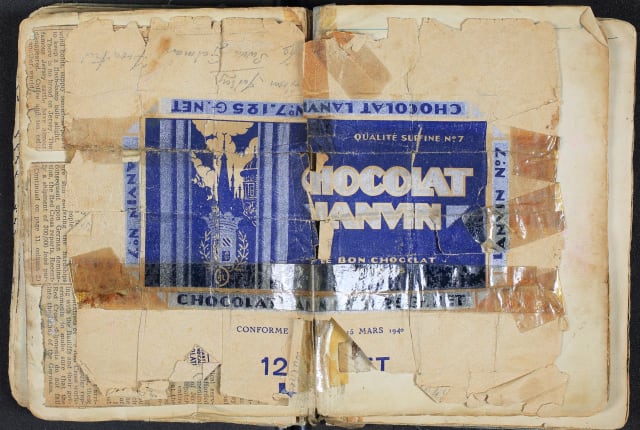

First day cover with the set of six red 1d. stamps, postmarks, registered mail label, and name and address of Hedy Bercu_

What escaped the Germans’ notice was that embedded in the design was something far more subversive. In each of the four corners of each stamp, Rybot included a tiny letter ‘A’ – a secret message of resistance. These letters, he later revealed, stood for the Latin phrase Ad Avernum Adolfe Atrox (To Hell with you, Atrocious Adolf). A second issue of green ½d stamps, released in January 1942, featured a similar secret message: ‘AA’ – ‘Atrocious Adolf’ – in the top corners – and ‘BB’ – ‘Bloody Benito’, a jab at Mussolini – in the bottom corners.

This was Rybot’s secret protest against the Nazi regime, hidden in plain sight. However, it is what is written on the envelope that elevates it from something of philatelic interest, to a document of archival importance. Printed on the front is the name and address: ‘Miss Hedy Bercu, 28 New Street, St. Helier, Jersey, C.I.’

Close-up of one of Rybot's red 1d stamps. Seen in each corner is an 'A', which formed part of Rybot's secret message against Hitler

Hedy Bercu was born in Vienna in 1919 into a Jewish family. In 1938, as the Nazi regime tightened its grip on Austria, she left her homeland and travelled to Jersey, arriving in November with a passport issued just two months earlier, which listed her full name as ‘Hedwig Bercu-Goldenberg’. In Jersey, she found work as a cook and settled into domestic service.

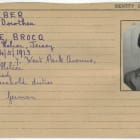

Like other non-British immigrants, Hedy was required to register with the Office of Immigration under the Aliens Restriction Act. A card was created, noting her arrival, movements, and eventual address at 28, New Street, St Helier – the very address written on the envelope now in our care at Jersey Archive. A microfilmed copy of Hedy’s card, also held by the Archive, is one of the few surviving records of her life in Jersey.

By July 1940, when German forces occupied the Channel Islands, Hedy was still living at New Street. In October of that year, she complied with new German regulations requiring Jewish residents to register their identity. Her Registration card was stamped with a red ‘J’ – a mark that set her apart and placed her in danger.

Front of Hedy Bercu's Aliens Registration card, showing the large 'J'

In an attempt to distance herself from her Jewish background, she claimed to be the illegitimate daughter of a Protestant woman, who later married a Romanian Jew. Hedy’s statement was recorded by Chief Aliens Officer Clifford Orange, but her Jewish identity was now an official matter of record.

Despite that, Hedy secured a job working for the German authorities in the transport department, where her knowledge of German made her a useful interpreter. This role gave her access to resources most Islanders lacked. According to later testimonies, she used her access to obtain petrol coupons to help local doctors to continue their work. But while she helped others, her own position became increasingly perilous.

Hedy Bercu's registration as a Jew in October 1940, with note by Clifford Orange regarding her Jewish heritage

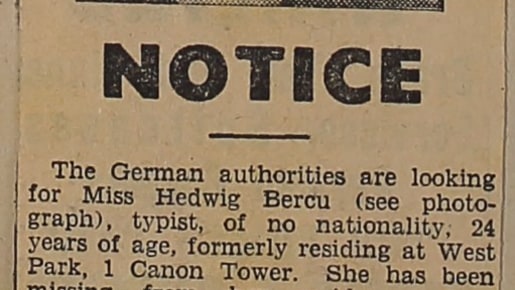

Accused of smuggling petrol coupons, Hedy made a desperate decision. She faked her own suicide and vanished on 4 November 1943. The German authorities responded quickly and her photograph – taken from her immigration records – appeared in the Evening Post alongside a stern warning: “Anyone concealing Miss Bercu or aiding her in any other manner makes himself liable to punishment.” The authorities assumed she had escaped to France, as a note to that effect appears on her Registration card in 1944. But they were wrong. Hedy was still in Jersey.

Notice published in the Evening Post in Nov 1943 appealing for information regarding the whereabouts of Hedy Bercu

For 18 months, she lived in hiding, first sheltered by Bozena Kotyzova, a Czech national, and then by a local woman named Dorothea Weber, née Le Brocq. Dorothea’s husband, an Austrian baker, had been conscripted into the German army in 1942, leaving her alone in their house at 7, West Park Avenue. There, Hedy was concealed for the rest of the war, at enormous risk to all involved. Food was brought by a German soldier, Kurt Rümmele, who was in a relationship with Hedy.

7, West Park Avenue, where Dorothea Weber hid Hedy Bercu during the Occupation

The danger increased in the summer of 1944. A list of 18 escapees, including Hedy, was circulated to the local police. She remained hidden and when Liberation came in May 1945, she re-emerged alive and free. On 14 May, she reported to the Aliens Office. Her record was updated to include her hiding address, and in the months that followed, she resumed her work in domestic service, first at Green Banks in St Saviour, and then at La Ferrière. She worked for two different families, as a cook and a children’s nurse.

Record of Hedy's movements from her arrival in Jersey in Nov 1938 through to 14 May 1945, when she was finally able to come out of hiding

In early 1947, Hedy left Jersey to be near the prisoner-of-war camp in the south of England where Kurt Rümmele was interned after the war. They married in 1949, and Hedy converted to Protestantism. The couple had three children before his untimely death in 1956. She remained in Germany, raising her family. Dorothea Weber’s act of bravery would not be formally recognised until many years later. In 2016, she was named Righteous Among the Nations in a national memorial, and in 2018, she was honoured as a British Hero of the Holocaust.

Plaque at 7, West Park Avenue, commemorating the life and bravery of Dorothea Weber

There was no letter inside the envelope when it arrived at Jersey Archive. This mystery is part of what makes it so intriguing as an object. What was once inside? Was it a letter from a friend? An official letter from the authorities? Or simply a commemorative first day cover, kept for its philatelic interest? We do not know, but the object remains full of meaning.

The envelope links together threads of resistance, secrecy and survival. It connects Rybot’s secret protest to the defiance of a woman who risked everything by staying alive and of those brave islanders, like Dorothea Weber, who risked their own lives and freedom to help others.

Objects like this bring to the fore stories that are easy to lose. Hedy’s life in Jersey was almost invisible for 18 months because it had to be. But the records held by Jersey Archive tell her story, from a red-stamped Registration card to a newspaper notice, and a return from hiding after Liberation to a life rebuilt in a new country. The envelope adds another piece to that puzzle, and ensures that Hedy Bercu, once hidden, is remembered.

Stolperstein on the pavement outside 28, New Street, placed in memory of Hedy Bercu

History

The German Occupation

A brief history of the German Occupation of Jersey, from 1 July 1940 to 9 May 1945

History

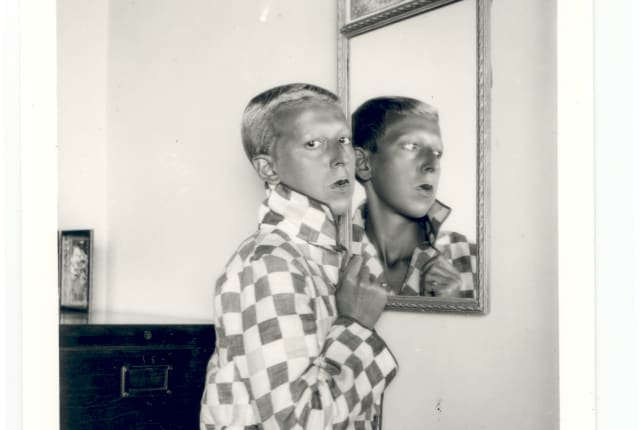

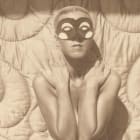

Claude Cahun and Jersey

Claude Cahun (1894-1954) was an artist, photographer and writer, best known today for surreal self-portrait photographs.

History

Jersey in the Early Medieval Period

Discover the history of Jersey during the Viking era, we'll take a closer look at the political and cultural landscape.

History

Island at war

The Channel Islands were occupied by Nazi forces during World War II, read one woman's extraordinary story.

History

The Black Dog of Bouley Bay

Although it is very small, just nine miles by five, Jersey has an incredibly rich history and heritage of myths and legends.

History

Corn riots

Learn about the corn riots of 1769, why they happened and how this public protest inspired change.