Oysters have long been an important part of Jersey, not only its fishing industry but also its wider culture, heritage, and identity. They connect the Island to its past and continue to influence its economy and cuisine today.

In the mid-1800s a long stretch of coastline in the east of Jersey was named after the Visit of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in September 1846. The Royal Bay of Grouville became the centre of the oyster industry, with millions exported annually to England and sent primarily to London, where they were sold as everyday food.

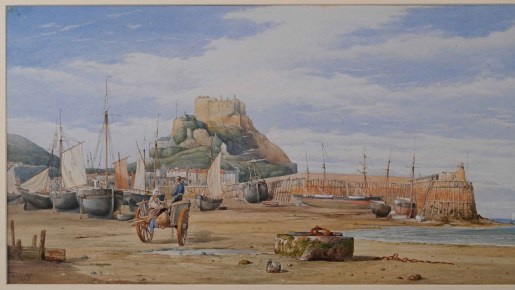

Mont Orgueil Castle from Harbour with fishing boats – watercolour painting by James F Draper - Courtesy of the Société Jersiaise

But the story of oysters in Jersey began at least 6,000 years ago. Archaeological evidence reveals that oysters have been consumed since the Neolithic period. Their shells are often found during archaeological digs, suggesting that oysters were an important part of the diet of early settlers.

During Roman times, it is likely that oysters were cultivated or at least gathered in significant quantities. Remnants of oyster shells can be found in medieval architecture – the walls of Mont Orgueil Castle, constructed in the 13th century. This illustrates just how ingrained oysters have been in the Island’s daily life over the centuries.

By the Middle Ages, “native” oysters were being fished from the southeast coast of Jersey. In 1606, Jersey’s Governor, Sir John Peyton, attempted to claim the Gorey oyster beds as property of the Crown. However, the Royal Court of Jersey ruled against him, declaring instead that every Islander had the right to work the beds. This early dispute shows just how valuable oysters were.

In 1685, Philippe Dumaresq, Seigneur of Samarès, produced “A Survey of the Island of Jersey” with a map in which he marked the location of the Gorey beds. He noted their excellent quality, describing them as “very large and good Oisters” lying four or five miles offshore.

By the 18th century, oyster fishing was flourishing. The Royal Court began regulating the beds, restricting dredging to from May to August. Further legislation was passed in 1771.

In 1797, rich new banks were discovered stretching between Jersey and the French Island of Chausey, extending from Cap Rozel in the north to the Minquiers in the south, between three and nine miles from the French coast. These were even explored and dredged during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, underlining the immense demand for oysters and the determination of Jersey fishermen.

The oyster industry truly came into its own in the 19th century, a period that historians often call the golden age of Jersey’s oyster trade. Between 1810 and 1871, it is estimated that Jersey exported around two billion oysters to England:

In 1810, a formal fishery was established to supply oyster companies in Kent and Sussex. Collecting oysters involved dredging – the native flat oysters attached themselves to rocks and stones in shallow waters. Growing from a tiny “spat” only 0.3mm in size to an edible oyster of about 65mm took around four years. These oysters were not the luxury they are today. Instead, they were considered everyday fare, cheap and filling for the working classes of London.

Part of Gorey Harbour during the Oyster Fishery, 1833 painting by Jean Le Capelain Jersey Heritage Collections

The scale of the industry quickly expanded. By 1822, over 300 vessels with nearly 2,000 seamen, many of them English, were dredging the banks, while more than 1,000 women were employed onshore packing and sorting oysters. To prevent the catch deteriorating, the work had to be done with speed. Sadly, the women of Jersey’s oyster industry remain nameless and largely forgotten.

Hundreds of shore workers were employed as basket fillers, carriers, lifters and washers, sometimes labouring by moonlight. The shore was a hive of activity during the second half of the oyster season, which lasted from February to April.

Mannequins, created by Giles Bois and Val Nelson, depicting a family employed on the Oyster fishery – on display in the Maritime Museum.

When the fleet returned with their catches, the oysters were dumped in a ‘park’, marked by a stake, and were then sorted into those fit for the English markets and those to be retained for local tables. The export catch was then sent by fast vessel to English beds, where they were fattened before going on to London.

Processing was carried out in simple sheds along the shore at Gorey. The catch was then shipped to England and laid down in Kentish or Essex oyster beds to be fattened more before being sold.

The oyster industry brought economic prosperity to Jersey, and the oyster boom transformed Gorey. With so many ships needing facilities, £16,000 was spent on building a pier and improving Gorey Harbour. By the end of the 1820s new jetties were also constructed at Bouley Bay and Rozel, for about 70 vessels, and a quay was built at La Rocque to shelter 40 vessels.

The images below are from the sketchbook of Jean Le Capelain showing the people of the oyster fishing industry.

The influx of immigrant fishermen from England led to the creation of Gorey Village – built behind the Common, on low-lying marshy land. This new settlement, however, was plagued by poor drainage and fell victim to a cholera epidemic in 1832.

Gouray Church was built on the hill to serve the spiritual needs of the growing English-speaking community, and a National School was established for the children of the area. The oyster industry also led to a rise of shipyards, building and repairing oyster boats. Three of the earliest, active in the 1820s, were Edward Le Huquet, John Filleul and George Lane. In the late 1830s Filleul and de la Mare built three cutters at La Rocque.

The prosperity of Jersey’s oystermen soon attracted the envy of French fishermen. Fierce rivalries developed, leading to violent clashes at sea, including a French warship firing a broadside amongst the “Jersey Oystermen”, the seizure of Oyster boats on the high seas and captured fishermen being beaten up.

In the 1820s, two British naval ships HMS Fly and HMS Helicon were dispatched to protect Jersey’s fleet from French aggression. The situation reached a dramatic peak in 1828 in a daring confrontation – the entire Jersey oyster fleet (about 300 vessels) sailed for France, boarded the warships, retook an oyster cutter and brought her back in triumph. Several lives were lost, and the incident was reported nationally, in The Sunday Times.

Tensions with France led to the signing of the 1824 Convention, which restricted British access to oyster grounds within six miles of the French coast. This deal marked the beginning of the industry’s decline.

By the 1830s, new laws were introduced locally to regulate fishing, including minimum sizes, closed seasons, and heavy fines. Yet even these measures could not prevent overfishing, disputes, and further decline. And violent incidents still occurred – in March 1836 George Bennett master of the oyster cutter, Frolic, was shot dead by someone on board the French Government Cutter, L’Ecurel.

At its peak, the industry was Jersey’s most important export. An oyster canning factory was established, in a house on Gorey Pier, around 1837-39, and shipyards thrived by building and repairing oyster boats.

Overfishing, combined with political restrictions, economic downturns, and competition from new oyster beds elsewhere, spelled disaster. The economic boom ended abruptly in the 1850s – because of the collapse of world trade and the cod fishing industry, plus the inability of the shipbuilding industry to make the change from sails and wooden hulls to steam and iron, a decline in the support Britain was prepared to give to the Island.

With the discovery of new beds in the English Channel between Cherbourg and Dunkirk, during the 1850s there was a brief revival in the oyster industry, but after 1855, with increased regulation and stricter enforcement of the closed season, the industry again went into decline. In 1856 the fleet had grown to 256 boats, with 1,300 crewmen, and the export of 180,000 tubs of fresh oysters brought in £35,000. By 1860 there were only 165 boats, and the catch was half what it was at its peak. Three years later the fleet was down to 46 boats, and the catch was only 9,800 tubs. By 1871 the once-mighty fleet was reduced to just six boats, and within a decade Jersey’s oyster industry had collapsed entirely.

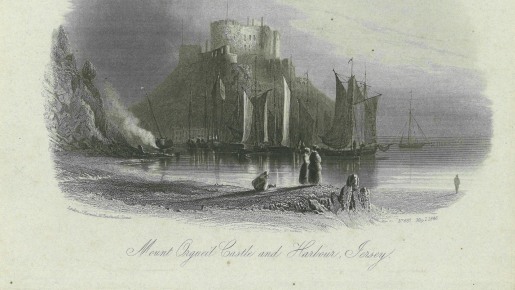

Mount (sic) Orgueil Castle and Harbour. Engraved print by J Harwood, London, 1846 Courtesy of the Lord Coutanche Library Archive, Société Jersiaise

A new oyster bank was discovered by the Roches Douvres in 1877. The States gave a reward to the captains of the two oyster cutters involved in the discovery. But the bank proved to be too deep to dredge effectively and the interest amongst the entrepreneurial class within the Island was no longer there. There was no longer the infrastructure to service an oyster industry. By the 1880s, the few oyster boats left were based in North Wales or in Shoreham and by the end of the century the Jersey oyster fleet had simply become a memory.

With broader economic struggles in the Island, three bank failures between 1873 and 1886 had the effect of further accelerating the decline. Poor economic prospects led many Jersey people to leave the Island seeking better opportunities abroad.

For most of the 20th century, oyster fishing in Jersey was negligible. After nearly a century of decline, oyster farming has since re-emerged, but this time with the cultivation of the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas), now the dominant species in Jersey. Unlike the native flat oyster, these thrive in aquaculture systems and grow well in Jersey’s clean, nutrient-rich waters.

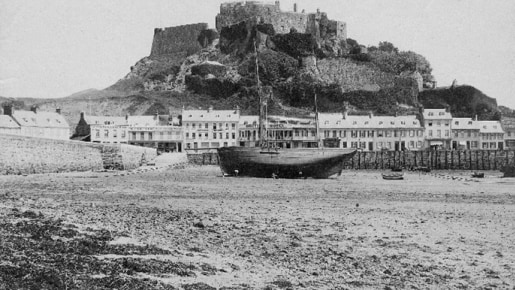

View of Mont Orgueil Castle and Gorey harbour, pre-1893, at low tide with Oyster Cutters Courtesy of the Société Jersiaise Photographic Archive

Today, oyster cultivation is concentrated in Grouville Bay, beneath the shadow of Mont Orgueil Castle. Oysters are filter feeders – taking in large amounts of water to feed and breathe.

With one of the largest tidal ranges in the world, twice a day Jersey doubles in size and its 48-mile coastline is transformed – revealing ancient causeways, tidal Islands and sea beds that resemble moonscapes. Jersey offers oysters an extraordinary environment – they spend half their lives exposed to air when the tide recedes and the other half submerged in some of Europe’s cleanest seawater. This unique rhythm strengthens the oysters, hardening their shells and ensuring they remain robust and fresh when harvested. The natural flushing action of the tide also keeps the waters pristine, contributing to the superior taste of Jersey oysters.

Modern oyster farming in Grouville Bay covers around 35 hectares, with several smaller holding areas closer to the shore. The oysters are tended carefully, bagged on metal trestles, and moved as they grow. Before export, they are left exposed for at least two weeks to prepare them for transport, reducing stress and ensuring they arrive alive and fresh at their destinations. Processing, grading, and purification take place in a nearby plant, where between 50 and 60 million oysters pass through each year. Around 1,000 tonnes of Pacific oysters are harvested annually, with most exported to France and the UK.

This new chapter in Jersey’s oyster story is led by the Jersey Oyster Company, owned by Chris Le Masurier, a third-generation oyster farmer. Since the late 1990s, Le Masurier has expanded the business into one of Europe’s most respected oyster producers. His oysters are sold year-round and celebrated not only for their flavour but also for the sustainable and environmentally friendly way in which they are farmed.

The history of oysters in Jersey is more than a story of fishing and farming. It reflects the Island’s changing fortunes, its battles for economic survival, and its close ties with Britain and France. The rise and fall of the 19th-century industry shaped Gorey Village and Harbour and inspired the building of Gouray church. It created job opportunities for women and migrants, fostered shipbuilding, and provoked international disputes. At the same time, its collapse highlighted the dangers of overfishing, poor regulation, and political compromise.

Today’s revived oyster industry is smaller, more sustainable, and more specialised, but it carries with it the echoes of the past.

To eat one is to taste not just the sea, but the spirit of Jersey itself.

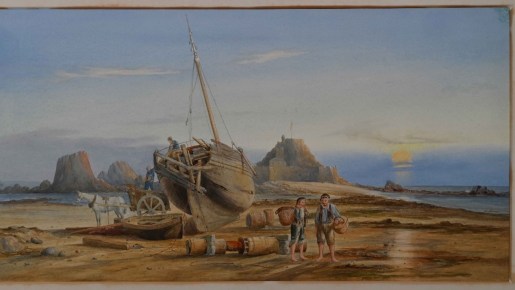

Elizabeth Castle with damaged fishing vessel, horse and cart – water colour painting by James F Draper - Courtesy of the Société Jersiaise

In Jersey today, oysters are available in Beresford Street fish market in St Helier, and at L’Etacq in St Ouen, and on the menus of many of the Island’s top restaurants. Diners enjoy them raw with a squeeze of lemon juice, a splash of shallot vinegar, or even a dash of Tabasco or vodka. An oyster should not simply be swallowed whole: chewing releases the full flavour and allows the salty “liquor” inside the shell to mingle with the meat.

Locally, oysters are often served with chilled white wine – Champagne, Chablis or Muscadet – or even a Jersey gin. Oysters can also be enjoyed cooked in a variety of ways but if cooked for too long, oysters will toughen up. “Angels on Horseback” is prepared by rolling shucked oysters in bacon and then baking in an oven. Oysters can be fried tempura style; poached in water, wine or broth for 4-5 minutes until the oyster meat firms up; chargrilled with unsalted butter, parsley, lemon zest and garlic; steamed; oven-baked; etc. Each method alters their texture and flavour but retains their rich nutritional value.

Oysters have long been associated with romance – often reputed to be aphrodisiacs. Modern science suggests there may be some truth to this reputation: oysters contain unique amino acids that stimulate sex hormones, potentially enhancing libido. Whether eaten for health, flavour, or romance, oysters remain one of nature’s most fascinating foods.