Cider was the Island’s biggest export and the “national crop” well before the arrival of the Jersey Royal potato. The quality of both Jersey apples and cider was held in high esteem in France and the UK, but the industry eventually went into decline and only a handful of orchards remain today

Thankfully, today there is a growing interest in cider-making and the more unusual local varieties of apples. A small orchard was planted at Hamptonne in 1991 and these apple trees now provide fruit for the annual cider-making festival.The varieties in the orchard include Côtard, Petit Romeril, Gros Romeril, Têtard, Petit France, Gros France, Gros Pigeonnet, Nièr Binet, Late Rouget, Caplyi, Douces Dames and Belles Filles.

These are a selection of sweet, bittersweet and bittersharp apples, which when mixed together provide a good balance for cider making. Although good for cider these apples would be very bitter if eaten raw and have a very different taste from those bought in shops.

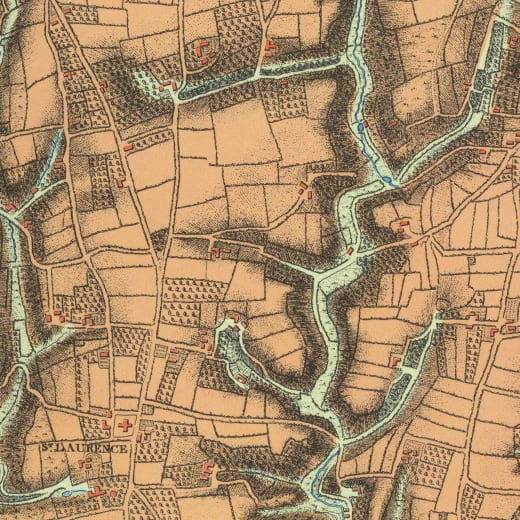

The Hamptonne orchard

In 1859, a list of was made of cider apples grown in Jersey, including Noir Binet, Petit Jean, Limon, Romeril, Amer, Pepin Jacob, Carré, Bretagne and de France.

In 1970 the Société Jersiaise published a list of named apple varieties found in Jersey, known as the ‘Pommage’. It included around 60 varieties with a description of their taste, colouring and uses.

Sadly, since the Pommage was published, most varieties have been lost. The Jersey Cider Orchard Trust was formed in 1989 to try and preserve some of the local apple varieties and new orchards were planted in Trinity and at Hamptonne Country Life Museum.

Apple varieties, image from the JEP

Cider Making

Traditional cider is made from a mix of bittersweet, bittersharp, and sweet varieties of apples. It is the balance between these that produces the individual taste of different ciders. This traditional cider is very different from many of the ciders sold in pubs today. The lack of sugar content meant that it had a drier – quite acidic – flavour.

Each maker had their own recipe, and this meant that there could be a big difference in both taste and quality. Poorly made cider could be sour, sharp and strong in flavour while the considerable strength of some local varieties could produce an effect like being kicked by a horse!

Because of its widespread production in the farming community, cider often formed part of a farm labourer’s allowance in the past. Where farmers were either unwilling or unable to produce good quality cider, casual labourers could be hard to get.

By the mid-18th century cider had become one of Jersey’s important exports and this led to the planting of sheltered orchards where there had previously been open spaces – by the early 19th century up to a quarter of the island was given over to apple trees. Later in the century, this export industry went into decline although farmers continued to produce for local consumption.

A common feature in most Island farms in this period was the circular, granite trough in which the apples were crushed, and the oak press.

A typical example of a Jersey apple crusher can be seen in Le Pressoir (the Cider Barn) at Hamptonne and is used annually for the demonstration of traditional cider making at La Faîs’sie d’Cidre.

Milling/Crushing the Apples

Once the apples are gathered, they are left for 2-3 weeks to allow some of the moisture to evaporate. This concentrates the natural sugar level in the apple which in turn increases the alcohol content of the cider.

As cider apples are hard, to extract the juice they first need to be crushed and then pressed.

Crushing or Milling is a slow process. The apples are placed in the circular trough where they are crushed to a pulp by a large wheel pulled around by a horse. It can take half an hour to carry out one crush. The troughs are usually made from granite from Chausey – the French Channel Island – because it is easier to carve than Jersey granite.

As the apples are reduced to a coarse brown pulp a couple of buckets of water are added to prevent the pulp becoming too sticky and unworkable; this also adds between 10 and 15% to the bulk.

At Hamptonne the crusher is used each October at La Faîs’sie d’Cidre when approximately 1 tonne of apples (80 bags) are crushed for each “press”.

Pressing

The pulp is transferred, using a wooden shovel, to the press. A layer of pulp is followed by a layer of straw, sacking and/or horse-hair cloth. At La Faîs’sie d’Cidre, sheets of Hessian are used. This process is repeated several times, making a layered effect. The pulp is known as “pomace” and the wrapped pomace is known as a ‘cheese’. A wooden ‘binder’ is used to keep the layers or ‘cheeses’ in place while they are being created. The weight of the layers causes the juice to flow.

Once all the layers are completed a large board is placed on top and the beam is lowered by turning the two screws simultaneously and the juice begins to run freely. As the juice is collected it is put into barrels, and the dry pulp can then be used as animal feed or fertilizer.

Various presses were used and the twin wooden screw press used at Hamptonne was copied from an 18th century example held in the museum collection. By the 19th century metal single-screw Presses were more common.

Fermentation

Once in the barrel, the juice begins to ferment, and sediment and froth is allowed to escape through the open bung hole. This process can take anything from several hours to days. The barrels are topped up with water to prevent too much air, which would ruin the juice. Gradually the froth changes colour from brown to white indicating that the juice is ‘working’.

This fermentation process can take a week or two in warm weather, or a few months in the winter. However, it was generally felt that a slow fermentation produced a better drink. Individual farmers often had their own methods for encouraging the fermentation process to work such as adding a handful of earth, meat, barley or wheat into the barrel. A small amount of beetroot juice could be added to make a warmer, more “pink” coloured cider. After initial fermentation the bung could be sealed with lime cement to keep out the air and encourage a second fermentation to occur over the next three months or more.

At Hamptonne after the cider making in October the cider remains in the barrels till the following year when it is drunk during the next La Faîs’sie d’Cidre.

Cider making has been a traditional pastime in Jersey for hundreds of years and many farmers have developed their own individual methods. This has ensured a wide variety of ciders each with their own unique taste. A “sparkling” cider can be made, by the addition of a small amount of sugar, but the cider needs to ferment in corked bottles.