Constructed in 1792, the Prince’s Tower (La Tour d’Auvergne) was one of the most outstanding and distinctive structures built in Jersey. Having stood for just over 130 years it was unceremoniously demolished in 1924. As a result, Jersey lost a famous landmark and a highly original and most distinguished contribution to the Gothic Revival.

As a Jerseyman and an adopted Prince D’Auvergne enjoyed a unique social status in the Island. He was an accomplished seaman and a scholar – a talented mathematician with a deep interest in scientific discovery. He held no strong religious beliefs and his library of 4,000 books suggests that he was an intellectual as well as a man of action. His architectural legacy to the Island, including the Prince’s Tower, show a man up to date with the latest fashions of his day, yet clearly looking back to an idealised medieval past for more than just his architectural inspiration. He aspired to live like a Lord, and was able to do so for some years. His obsession with succeeding to the principality of Bouillon cost him everything. His enchantment with Royalty and the aristocracy ran throughout his life and its humiliating finale still obscures his genuine achievements.

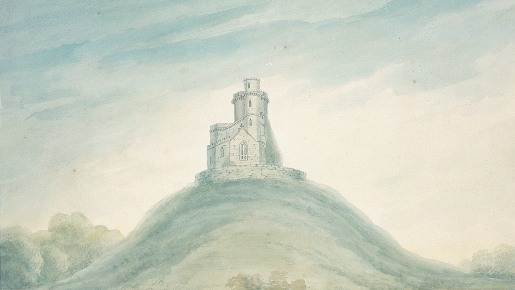

Watercolour of the Prince’s Tower, 1804.

Philippe d’Auvergne began the construction of the Prince’s Tower in 1792. He developed the site in a very personal and unique way producing the most flamboyant piece of Neo-Gothic architecture ever built in the Island. His design was inspirational and the way in which the medieval chapel and the physical constraints of the site were handled was ingenious. The Prince’s Tower gave the illusion of a miniature castle set on a hilltop.

In the middle of the 18th century numerous gothic follies sprang up in the English countryside inspired by medieval castles and monastic architecture. They were mostly decorative features in the grounds of country houses, or built for occasional use such as hunting or banqueting. The Prince’s Tower was different because despite its small size it was, in fact, a gothic country house, complete with essential facilities such as water supply, kitchen, banqueting room, chapel and a pleasure ground.

His choice of medieval-style building, with a circular crenellated tower may also have been for personal reasons. His adopted family name was ‘de la Tour d’Auvergne’, and the family emblem was a round castellated tower.

D’Auvergne only occupied the tower occasionally as his principal base was Mont Orgueil Castle and from 1802 he lived at a house named Bagatelle in St Saviour.

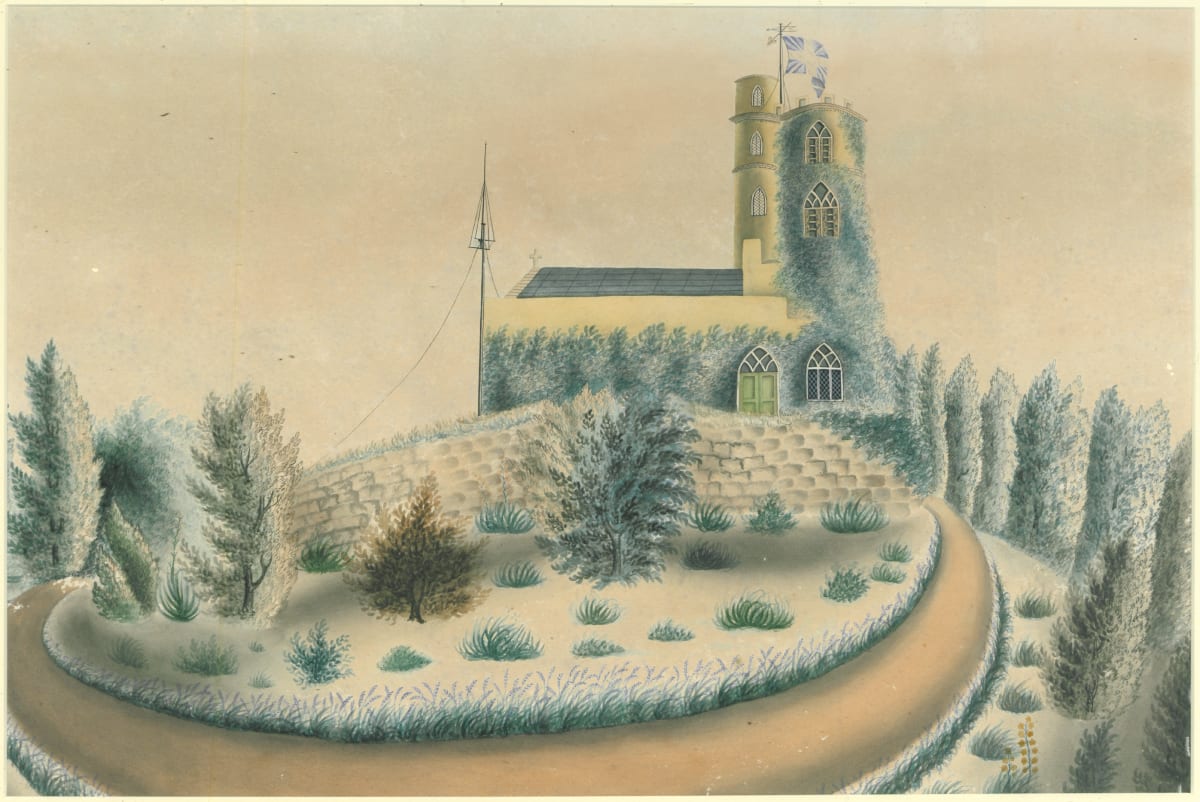

Image: Watercolour of the Prince’s Tower from the south, c 1810.

D’Auvergne recognised the strategic potential of La Hougue Bie and in 1792 established it as the central nerve of an important Island-wide signalling system. While each station would have been inter-visible with its immediate neighbours, there was only one elevated position from which the entire system could be controlled and that was from the Prince’s Tower.

A signalling mast was erected over the southwest corner of the medieval chapel. It was this mast which gave the Prince’s Tower its raison d’être. While there would be no practical justification for erecting a gothic extravaganza on the mound, the site was ideal for a signalling post.

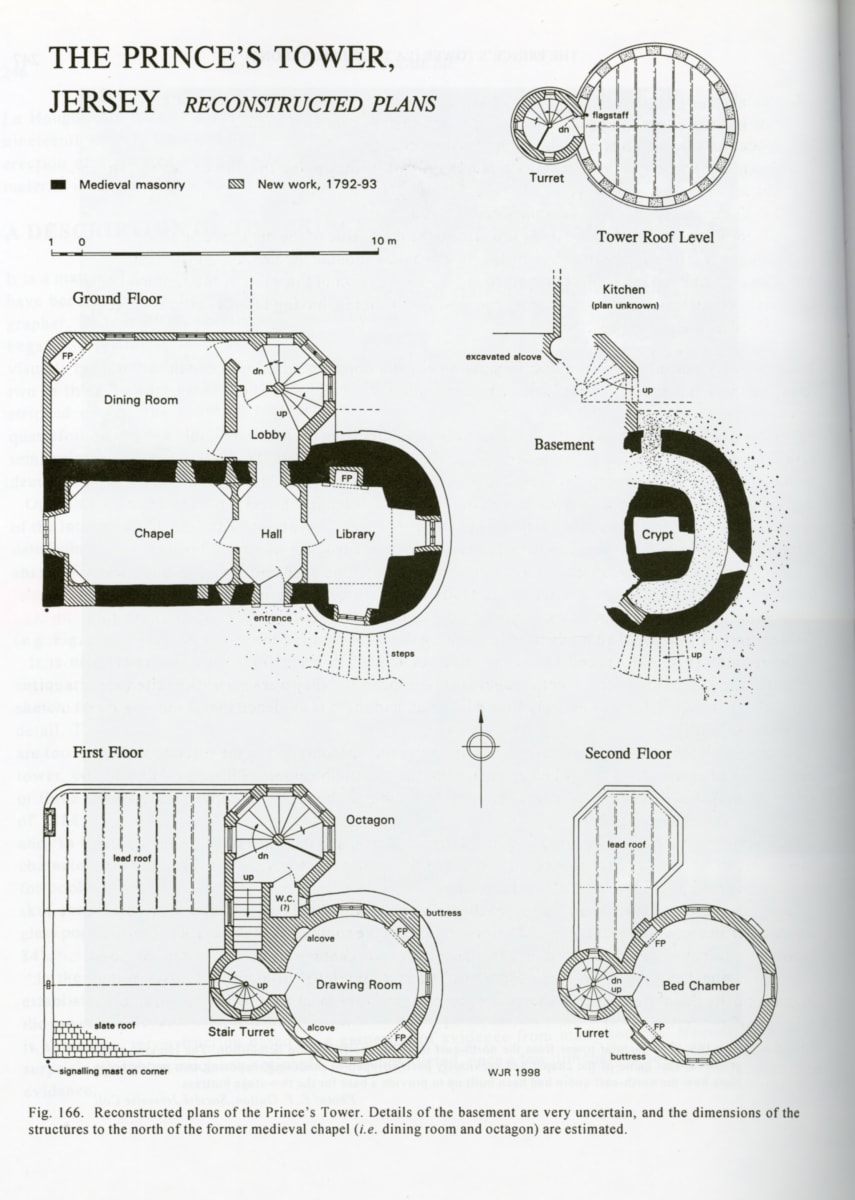

Unfortunately when the Prince’s Tower was demolished in 1924, no detailed plans or descriptions were made. We have however been able to use antiquarian illustrations and descriptions, and photographs taken just before it was demolished to help reconstruct its shape and design. Reused elements from around the site and fragments found during the 1990s excavations have also helped give an insight into the high quality of the decoration and furnishings – it seems no expense was spared.

The octagon and circular tower prior to demolition in 1924. Courtesy of the Société Jersiaise Photographic Archive

D’Auvergne dramatically altered the medieval chapel. An elaborate gothic doorway led into a tiny but formally planned octagonal entrance hall paved with Swanage limestone, all four corners contained round-headed alcoves which were a popular feature of d’Auvergne’s work. He converted the Jerusalem chapel into a library and inserted large windows to light the room and a fireplace in the north wall. Part of the medieval chapel was kept as a domestic chapel. It was a grand room on a small scale with a large gothic-style window and round-headed alcoves to display sculptures. The walls were painted in imitation marble and the floor was a chequered (Italian) marble pavement with a special rectangular feature where the altar stood.

Interior of the domestic chapel in the Prince’s Tower, c 1900 . Courtesy of the Société Jersiaise Photographic Archive

A stone paved lobby linked the medieval structure to a new brick-built range on the north side, which was based around an octagonal staircase hall. The spiral stairs led to all parts of the tower and were lit by a series of large quatrefoil windows. The octagon had a flat lead roof.

A dining room or banqueting hall was built against the north side of the medieval chapel. It had a crenellated parapet, two large windows in the north wall and a flat lead roof. The stone paved room had a fireplace in the north-west corner, it measured 5.8m by 4m and was serviced in the proper manner, with two doors at the eastern end where the ‘buffet’ (a counter for food and drink) was located between the two doors, following the usual Georgian arrangement.

A concealed staircase gave access to the kitchen which was located in the basement. It had a brick paved floor, large fireplace, oven and a well in the floor– dug when the tower was erected in 1792-3. Some of the foundations still remain buried in the mound today. The medieval chapel crypt may have been used as a cellar or left open as an object of antiquarian curiosity.

A circular three-stage stair-turret was built on top of the medieval chapel’s stone vaulted ceiling, destroying the belfry. Each level had three single-light pointed windows. The top stage had a door opening out onto the roof of a circular tower which was built directly on top of the medieval elliptical rotunda. This main tower had two floors each containing one magnificent round room (4.6m diameter). The first floor room with its panoramic views would have been the drawing room. The second floor room was the bed chamber. Each had three windows north, east and south, two fireplaces and alcoves built into the curving walls. A bowed door still survives and was reused as the entrance to the lodge.

The flat leaded roof of the tower was given a crenellated parapet and had uninterrupted views in all directions. It served initially as a lookout for d’Auvergnes’ signal station but may later have been regarded as a tiny prospect room. A flagstaff and weathervane were attached to the turret

Engraving of the Prince’s Tower pleasure ground, 1836

It is unclear when the Prince’s Tower and grounds were first opened as a public attraction. It is possible that d’Auvergne allowed people into the grounds when he owned the site. A letter dated October 2nd 1793 from Matthieu Gosset, Vicomte to d’Auvergne reports hundreds of people visiting on Sundays to watch the tower being built “ … I would advise you to have a Swiss at the Gate who should admit no one under a shilling (the prospect from the top is worth half a crown)… ”

After his death in 1816, d’Auvergne’s creditors sold La Hougue Bie for £350 to Major-General Hugh Mackay Gordon, the Lieutenant-Governor of Jersey. Gordon put the Tower into good condition and used it as an occasional residence. By 1822 the Prince’s Tower was no longer used as a private residence and was developing as a pleasure ground. Catering was being provided in the tower both for casual visitors and for shooting parties.

In the first half of the 19th century Jersey had become a fashionable Regency resort and residence for British ex-patriots. Improved road systems and developments in transport together with the aesthetic awareness of the Romantic era all contributed to making La Hougue Bie a popular local beauty spot and tourist attraction.

A gate lodge was built in the 1820s in the northeast corner of the site. This rustic thatched cottage functioned as a ticket office where visitors paid their admission charges. It was also a tearoom and the residence for the keeper of the grounds and his family.

The grounds, which were extensively planted by d’Auvergne, were now maturing and were adorned with various features such as a ‘bower’ (summer house), nesting boxes for doves, peacocks, wrought iron fences, tree protectors, ornamental arch, stone features (font), urns and seats, flag pole and the mitred figure of a bishop with his hand raised in blessing.

The site had become so popular that facilities were improved in the 1830s. The entrance lodge was extended to create a new building which became known as the Prince’s Tower Hotel. The new two-storey hotel provided accommodation and banqueting facilities. An external wooden staircase and covered balcony led to the ballroom which occupied the whole of the upper floor and probably doubled as a tearoom by day. It was lit with brightly coloured large gothic windows, (a number of which survive today incorporated into the (office) lodge built in 1925). The ground floor had stables with large carriage doors and there were four servants’ rooms in the attic.

Prince’s Tower Hotel from the northwest, c 1910. Courtesy of the Société Jersiaise Photographic Archive

The hotel owners dug a well, a toilet and incinerator into the eastern side of the Neolithic mound. Remains of these were discovered during archaeological excavations in the 1990s.

The old rustic lodge was rebuilt around 1845 as a two-storey house with pointed gothic windows. It housed the hotel bar and bedrooms. A bowling alley was constructed in a separate building. The Prince’s Tower Hotel soon became a popular venue for eating, drinking and dancing and by the middle of the 19th century the hotel had acquired a reputation for revelry.

Wedding party. Photograph from a private collection

By this time the Prince’s Tower was regarded principally as an ornament in the hotel’s grounds. Although the condition of the Tower had deteriorated, the 19th century fascination with ruins made the building more rather than less attractive as a local beauty spot. The tourists and Sunday excursionists who came to the beauty spot climbed to the top to view the surrounding landscape and seascape from the upper rooms and roof leads. The view would have been breathtaking.

Dining Room. Courtesy of the Société Jersiaise Photographic Archive

Various antiquities were displayed in the grounds and sometime in the late 19th century the former domestic chapel in the Tower was turned into a private museum, where objects with ecclesiastical associations were displayed. The objects were displayed in order to enhance the antiquarian ambiance of the site. All over Europe this was an age of collecting, and antiquities were commonly handed over to local worthies for display in their homes and gardens.

The Prince’s Tower was very popular with artists, poets and musicians. Apart from Mont Orgueil and Elizabeth Castles it is probably the most illustrated building in Jersey. The paintings and sketches are all quite ‘atmospheric’ rather than accurate, many have been romanticised are more works of art than historical records.

By the late 19th century the Prince’s Tower had become derelict, covered with ivy, the coloured glass windows were falling to pieces and the dining room was roofless. Structurally, however, the building was still in good condition.

In 1912 the property was being vandalised and it was proposed that the States of Jersey should buy the site and restore it for the public. The States rejected the proposal by 28 votes to 14. Eventually in 1919 the Société Jersiaise purchased La Hougue Bie for £750. The original intention of the Société Jersiaise was to restore the chapel and consolidate the Tower. However, a delay of five years caused by an un-expired tenancy agreement saw a change of attitude. In 1924 a restoration committee was set up which decided that d’Auvergne’s gothic building should be demolished and the fabric of the medieval chapel once again revealed to the public. It was claimed that ‘the tower was crushing under its weight the chapels upon which it had been so unscientifically erected. In fact the state of the whole group……we were likely to lose tower and chapels in one fell smash! It was therefore decided to save the chapels at the expense of the tower’

Evening Post 24 Sept 1924

A structural report contained nothing to suggest that the building was structurally unsafe or beyond repair. Nevertheless the findings were manipulated to sound the death knell for the Prince’s Tower.

At the time Georgian gothic was unfashionable in England and was almost universally regarded as worthless. The Société was also pursuing a great interest in the Island’s megalithic structures. As a result the urge to excavate the mound and desire to restore the chapels outweighed any consideration for the preservation of the Islands most outstanding monument of the Gothic Revival.

The Prince’s Tower was demolished at the cost of £135, during July and August 1924 against the wishes of the majority of Islanders. Tragically, d’Auvergne architectural legacy to Jersey was completely lost over the next 20 years. The Prince’s Tower was demolished, Mont Orgueil Castle was stripped out and his home at Bagatelle was blown up by a mutinous faction of the German army on 8 March 1945.

Image: The weathervane – bearing the d’Auvergne family coat of arms

A number of remnants from the Prince’s Tower era can still be found around La Hougue Bie today including the weathervane now on the roof of the lodge; some of the marble paving from the chapel was re-laid on the veranda of the lodge next to a bowed door, originally from the circular Tower’s bed chamber or drawing room and two 18th century keys still open the chapel doors.

Image: Model of the Prince’s Tower by Ben Ruthven-Taggart.